20/20 Vision for Rail Project Procurement

This post is an edited version of the presentation I delivered at the AusRAIL 2020 conference. I’ll share some some observations on the current state of the market for civil construction work, and the issues that are arising out of the way governments and other project owners have traditionally approached procurement and risk allocation. I’ll then look at various strategies governments and other project owners are pursuing to respond to current market conditions.

A profitless boom

The contracting market for major civil construction works on Australia’s east coast has become fraught – for project owners, major contractors, and the rest of the supply chain.

Rail sector projects are getting bigger and more complex – just look at the number of rail projects currently being procured by Australian governments valued at more than $1 billion.

Yet despite rising contract values, major contractors are struggling to make them profitable.

There are many reasons for this. But the main reason is governments preference for competitively tendered fixed price contracts.

Our governments like to use contract forms that transfer a lot of difficult to price risks to the contractor, such as the risk of unexpected ground conditions, the risk of unexpected work arising from interfaces with utilities, and the risk of interfaces with government’s other contractors.

Tenderers will be asked to make sufficient allowance in their fixed price for the potential consequences of the risks that the government agency is seeking to allocate to them. Indeed the draft contract will typically include a warranty from the contractor that its price includes sufficient allowances for the risks that the contractor bears.

But what will happen if the tenderer adds an allowance to its price to fully cover the additional costs that it would incur if one of these risks eventuates (eg ground conditions are not as expected)? Well, its price will become uncompetitive and it will lose the tender to one of its competitors.

Contractor’s quickly learn that they won’t win tenders if they ‘fully price’ the risks. Rather, it they want to win the tender, they need to take a punt and hope that the risks don’t occur, or if they do that the contractor will be able to recover its additional costs through unrelated variation claims and the like.

So, other things being equal, the tenderer who takes the most optimistic view of the risks, or who underprices the risks the most, will win the tender.

Government agencies understand this dynamic and they use the competitive tendering process to extract the best value for money outcome that they can. And history has shown us that even during periods of unprecedented demand for rail sector civil engineering expertise, like what we have seen over the last 5 years, that there are usually plenty of contractors that are prepared to take very optimistic views on risk in order to win their next job.

But what are the odds of these optimistic views being correct?

The sad reality for complex mega rail projects, often involving the integration of technology and systems from multiple different suppliers, as well as complex third party interfaces, the chances of something going wrong are very high. And the cost consequences when things do go wrong on mega rail projects can be immense.

History tells us that mega projects usually mean mega losses for the construction companies involved.

So much so that most tier 1 contractors that play in the rail sector are saying enough is enough, and they are demanding a risk allocation reset for mega projects. Some are simply refusing to bid for projects that don’t offer appropriate cost and time relief for hard to price risks.

So how might governments and other project owners respond to this situation. Let me offer a few suggestions.

Strategy 1: PPPs where equity investors share more risk

Let me first explain how risk is typically allocated in a PPP structure.

Government enters into a PPP contract with a new special purpose PPP company that has been established by the successful bidding consortium.

Under this PPP contract most of the risks associated with the design, construction, financing, operation and maintenance of the infrastructure facility – let’s say a new metro line – are allocated to the PPP company.

Government retains some risks, such as the obligation to acquire and make available the agreed construction site, and the risk of challenges to the planning approval that government has obtained for the project, but most risks, let’s say 90% of the project risks, are transferred to the PPP company.

The PPP Company then enters into a fixed price Design and Construct Contract with its D&C contractor under which all of the risks associated with the design and construction of the project, other than those retained by the government agency, are transferred to the D&C contractor. Let’s say for arguments sake that these risks equate to 60% of the project risks.

The PPP Company also enters into a largely fixed price Operation & Maintenance Contract with its O&M contractor under which all of the risks associated with the operation and maintenance of the project, other than those retained by the government agency, are transferred to the O&M contractor. Let’s say for arguments sake that these risks equate to 20% of the project risks.

So, of the 90% of the project risks that were taken by the PPP company under the PPP contract, 80% have been transferred to its two contractors, leaving the PPP company with 10% of the project risk. This 10% is split between the PPP company’s debt financiers and its equity investors. Debt always takes less risk than equity, so let’s say the debt financiers take 3% and the equity investors take the remaining 7%.

The D&C Contractor and the O&M Contractor will offload some of the risks that they take, such as the risk of the facility or the construction works being damaged by a flood, fire or severe storm, to their insurers, but I haven’t tried to show that here for simplicity.

We could have long arguments about the percentages I have come up with, but for most service payment PPPs, where the State is taking demand risk, it looks something like this.

Who will take the risks that the D&C contractor will no longer take?

Now, for the reasons I explained earlier, D&C contractors are refusing to take various ‘hard to price’ risks that they previously took. So let’s say this translates to the D&C contractor’s share of the project risk reducing from 60% to 50%.

Who is going to take the 10% that the D&C Contractor will no longer take?

If we are in a traditional publicly funded project, where there is no private finance and government contracts directly with the D&C Contractor, there is only one option – government needs to take the risks that the D&C contractor will no longer take.

But a privately financed PPP deal provides further options, as the PPP company and its equity investors could also take some more risk.

I haven’t suggested that the debt financiers could take more risk, as project financiers aren’t interested in changes to the risk/reward profile for project finance.

Now, if the PPP company takes more risk, as I have shown in the below diagram, with the PPP company’s share of the project risk increasing from 10% to 13%, the PPP company will need to have more equity and less debt in its capital structure, to absorb the additional risk. Because equity is more expensive than debt, this will increase the PPP Co’s cost of capital.

The higher cost of capital will result in a higher service payment for government, so government would need to see the value for money in paying more in return for the transfer of some of the construction risk that would otherwise fall to government to the PPP company and its equity investors.

Many of the equity investors that I speak to don’t think that Treasury Departments will see the value in paying more for the equity investors to take more risk. But I see an opportunity for clever equity investors to win PPP tender processes by developing a capital structure that would allow the PPP company to share in some of the hard to price construction risks for a small additional cost to government that is seen by Treasury Departments to represent value for money.

I also see potential for privately finance to be combined with a collaborative alliance style risk allocation in a PPP contract, where:

the equity investors share the ‘pain’ of construction cost overruns via a reduction to the quarterly service payment payable under the PPP contract which then delivers a worse than usual equity return, and

the government agency takes the balance of the owner participant’s risk in the alliance.

Conversely, if the construction phase of the project is delivered under the target cost, the equity investors could share in the upside by way of an uplift to the quarterly service payment that then delivers a better than usual equity return.

Strategy 2: More contract packages ….. and new ways of sharing contract interface risk

The prevalence of mega-projects, and the small number of contractors in the Australian market capable of delivering mega projects, has seen governments break mega-projects up into several smaller contract packages, rather than combining them into a single package, as a way of de-risking the main package, or to enable smaller or more specialised contractors to compete in their own right and thereby expand the pool of bidders.

Recent examples of rail projects that have employed this strategy include Sydney Metro, Melbourne Metro, Cross River Rail and Gold Coast Light Rail.

But this strategy also creates a bunch of new risks for both government and its contractors.

Below are some suggestions on how these new risks could be better managed.

The above diagram shows a 3 package structure like that adopted on Sydney Metro Northwest, and that proposed for Sydney Metro Western Sydney Airport.

The government agency, shown in orange, enters into two publicly funded D&C Contracts for:

Package 1 – a tunnel package, and

Package 2 – a viaduct and surface civil works package,

The government agency then enters into a third contract – for the PPP package.

The government will need to make promises to the PPP company regarding the scope and timing of the interfacing works that will be performed by the package 1 and package 2 contractors. If these promises aren’t met, government will be liable to the PPP Co and left to recover from the defaulting package 1 or package 2 contractor.

Of course, each of the package 1 and package 2 contractors will seek to limit their liability by reference to the contract price for their package. Any liability that government has to the PPP company in excess of the cap on the defaulting P1 or P2 contractor’s liability remains with government agency.

This can be a significant risk for government if the value of package 1 or package 2, and hence the cap on liability of the package 1 or 2 contractor, is small relative to the government’s liability to the PPP company that has suffered loss as a result of the default. If the default causes a delay to service commencement under the PPP contract, the government’s liability to the PPP company for loss of revenue and additional financing costs can be massive.

Is there a better way?

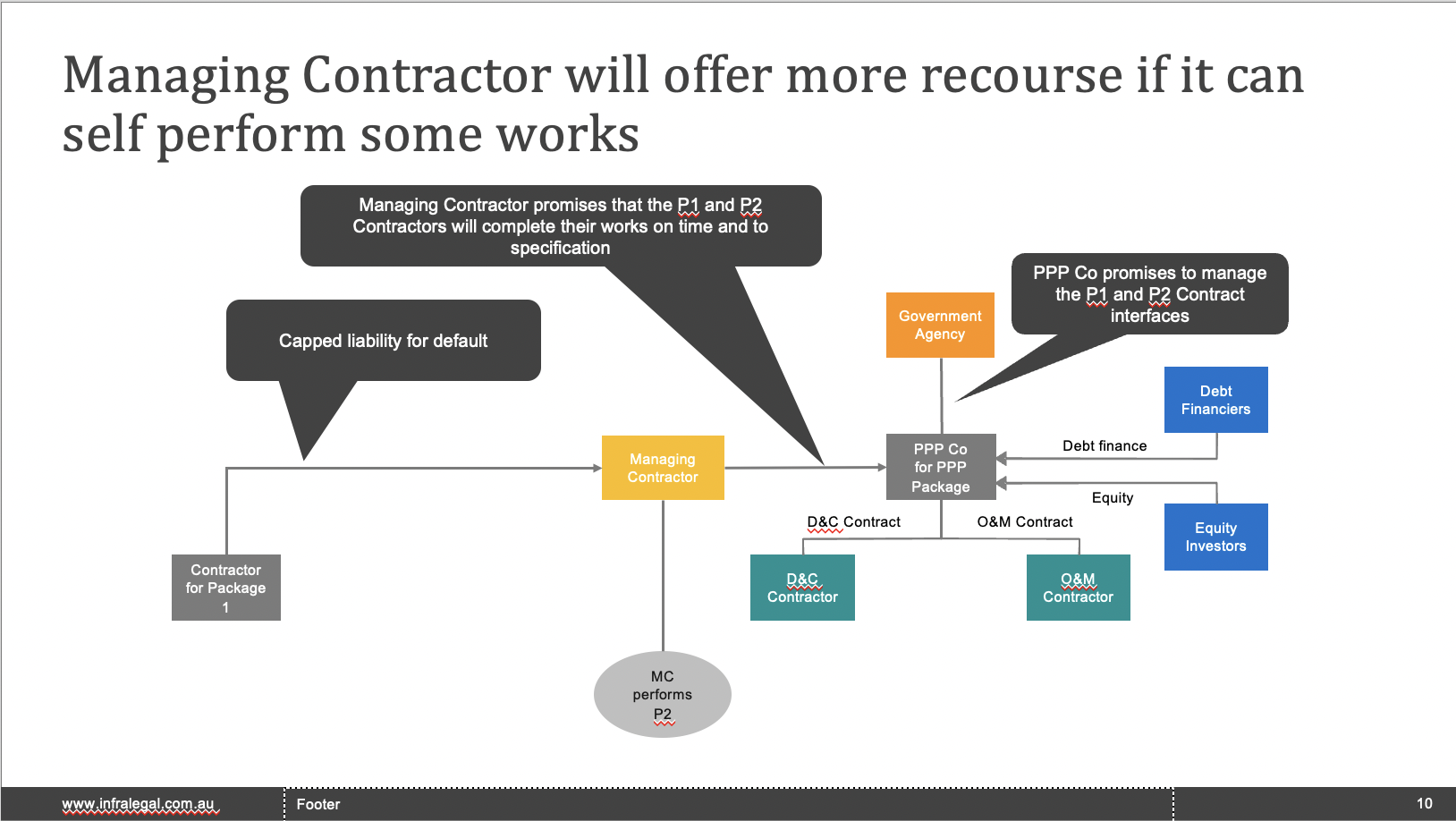

Is there a better way to manage contract interface risks, that would optimise the risk allocation as between the various parties? Perhaps the contract interface risks could be better managed by a PPP company that has both:

the expertise of a top tier ‘managing contractor’ (either through its employees, or through an outsourcing arrangement); and

recourse to a balance sheet, or additional equity, that can absorb the financial consequences of a failure to adequately manage these risks.

The second element is needed because of the PPP company’s use of limited recourse debt. It won’t be able to borrow the limited recourse debt unless its debt financiers are satisfied that the PPP company has either:

the ability to recover its losses from the managing contractor, or

the additional equity needed to absorb the additional contract interface risks.

Again, this presents another opportunity for equity investors to add value to a PPP by sharing more risk.

There are several top-tier ‘managing contractors’ in the Australian market. But managing contractors typically seek to limit their liability by reference to price they are paid for the performance of their services, which may not provide the PPP company with sufficient recourse.

One way to lift the limit on the managing contractor’s liability in relation to its managing contractor services might be:

for the managing contractor to also perform significant D&C services for the PPP company under a separate D&C contract – in this case package 2,

and for its potential liability across both contracts to be aggregated based on the combined value of the services it provides under both contracts.

As mentioned above, one of the reasons why governments are creating separate contract packages is to enable certain works to commence before the main contract package, in this case the PPP contract, is awarded. This creates a timing issue that would need to be addressed under the arrangements just discussed, as the early works contracts would be awarded by government ahead of the PPP contract.

The subsequent novation of the government’s rights and obligations under the early works contracts to the PPP company (or its managing contractor) is one potential solution to the timing issue.

Another approach to optimising the sharing of contract interface risk involves the government retaining it (in its contract with the PPP company), but then sharing it with a managing contractor. The managing contractor would be engaged by government to assist it to manage the contract interface risks.

This approach shields the PPP company’s equity investors and debt financiers from the contract interface risk. Consequently the PPP company avoids the need to have additional equity, or recourse to a balance sheet that can absorb the financial consequences of a failure of the PPP company or its managing contractor to adequately manage these risks.

This approach also avoids the timing issue mentioned above.

Strategy 3: Collaborative Contracting

Collaborative contracting is the term used to describe a family of contracting approaches that seek to address the problems that are inherent in traditional fixed price contracts.

There are inherent problems with traditional fixed price contracting that collaborative contracting seeks to address.

The first is the allocation of specific scope and risks to individual project participants, which encourages the blame game, rather than problem solving, when things go wrong.

Second, fixed price contracts are inherently adversarial as they financially motivate the contractor to minimise the cost of delivering the agreed scope, in order to maximise its profit margin, even if doing more would ultimately reduce the project owner’s costs of deliver better project outcomes.

Third, conventional fixed price contracts provide no incentive for project participants to minimise the cost impacts of changes to the project. Rather, they provide an opportunity for the incumbent project participants to charge ‘monopoly’ prices for the additional work, as it is usually impractical for the owner to competitively tender the extra work.

For these reasons, traditional fixed price contracts result in the commercial interests of the non-owner participants being misaligned with those of the project owner.

Collaborative contracting seek to address these problems by adopting alternative commercial frameworks that better align the commercial interest of the non-owner participants with those of the project owner

There are a range of collaborative contracting approaches that fall on a spectrum, depending on how they approach key issues such as cost risk, time risk, quality, liability and decision making. The above diagram shows the main collaborative contracting models, and where they sit on the spectrum from less collaborative on the left, to more collaborative on the right. The key issues on which the various models tend to differ are shown by the icons in the bottom half of the slide.

If you are interested in better understanding the spectrum of collaborative contracting approaches, take a look at the report on collaborative contracting available via this link.

Strategy 4: More international contractors

International contractors, particularly Chinese, Japanese and American contractors, have been reluctant to enter the Australian market due to the risk/return equation available to contractors in the Australian market.

Australian governments are seeking to address these concerns and attract more international contractors to our market. They could accelerate this process by doing three things:

Firstly, that could speed up the process of procurement reform to reduce bidding costs and improve the contractor’s perceived returns.

Second, Governments could reduce the barriers to foreign contractors entering and competing effectively in our market, and eliminate perceptions of bias against international contractors.

Thirdly, Governments could reduce the perceived threat to contractor profits represented by client/buyer power in Australia by moving to more balanced, less client-friendly risk allocations and contract forms.

Conclusion

To wrap up, we have a fraught market for civil engineering works and services, due to the strong levels of demand from governments.

The profitless boom that contractors have experience is likely to result in a risk allocation reset, involving

PPPs where equity investors share more risk;

smarter ways of interface risks arising from multiple contract packages;

more collaborative forms of contracting; and

reforms to attract more international contractors.